This article was originally published on Devex on June 2, 2021

Twenty-one years into the 21st century, there is clearly a gap between what is and what should be when it comes to diversity, equity, and inclusion practices in the international development and humanitarian assistance sector. For years, an inability — or unwillingness — to collect public, sector-wide data on diversity hid the pervasiveness of the problem and thus limited the extent to which individual organizations addressed it.

Last summer, Social Impact’s CEO and initiator of the BRIDGE Initiative, Shiro Gnanaselvam, told us she was frustrated by this. “I wanted to benchmark our diversity profile, policies, and practices to something comparable, but that something simply didn’t exist.”

Motivated to bridge this gap, she called her friend and former colleague Alicia Phillips Mandaville, now senior vice president of programs at the International Research and Exchanges Board, with an idea.

Before long, the two had formed a volunteer coalition, led by Social Impact, IREX, Humentum, and the WILD Network and supported by a dedicated working group of partners — Dexis Consulting Group, National Endowment for Democracy, Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation, Solidarity Center, Orbis International, and InterAction.

The group’s goal was to develop a snapshot of diversity at the headquarters of United States-based organizations. The survey would collect race, gender, and disability data for staff, management, heads of organization, and boards as well as explore the diversity, equity, and inclusion policies and practices of responding organizations.

Working together, the group designed and implemented

the Benchmarking Race, Inclusion, and Diversity in Global Engagement, or BRIDGE, survey, an institutional survey of U.S.-based development and humanitarian organizations. Between March and April 2021, the online survey was sent to human resources executives at 381 organizations in the sector, of which 166 responded. This represents a 44% response rate, well above average for this type of survey.

While many results are not surprising, the data paints a startling picture of inequity and uneven power dynamics. Here is a snapshot of what we found:

1. Racial inequity is pervasive at higher levels of organizations

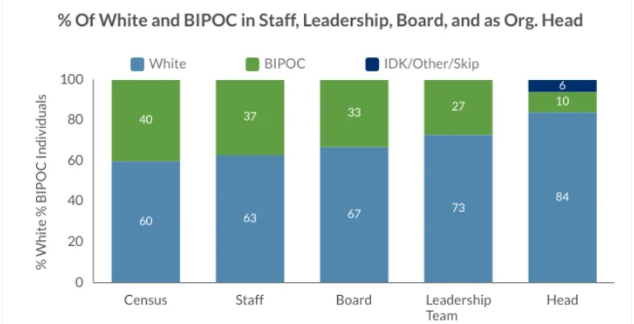

While the racial composition of staff — white vs. BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, and people of color] — more or less mirrors the U.S. population, this pattern does not hold at higher, more powerful levels of the organization. Only 27% of leadership teams and 10% of heads of organizations in our sector identify as BIPOC. Organization boards have slightly better BIPOC representation — approximately 33% — though this too is less than the general population.

Intersectionality and specificity paint an even more stark picture: only 4% of heads of organizations are BIPOC women even though they represent 20% of the general population, while LatinX individuals are under-represented at all levels of organizations in our sector.

2. Women disproportionately perform the work but are less represented at leadership levels

The international development and humanitarian assistance sector disproportionately attract women to its workforce, with 68% of staff identifying as female.

However, at the board, management team, or head of organization levels, the proportion of women declines to roughly 50%, more closely mirroring the U.S. population.

3. Most organizations do not have a DEI policy; even fewer address leadership diversity

A year after the protests following the murder of George Floyd, some 40% of organizations have issued a DEI statement. However, while 85% of responding organizations report that they have taken some steps with respect to DEI, only 26% had DEI policies in place — with a further 16% in the process of drafting one. This leaves a majority — 58% — of organizations with no DEI policy or tangible plans to create one.

Organizations that do have a DEI policy focused primarily on hiring, equitable compensation, inclusive workplace, and equitable performance appraisal. While slightly more than half of the small organizations that have an existing DEI policy included a focus on leadership diversity, more than 80% of organizations have no formal accountability mechanism to squarely address the biggest challenge identified by this survey: insufficient diversity at all leadership levels.

What do these findings mean?

It is clear that the makeup of who has a seat at the top tables must be rebalanced. A deeper question should be, what should a rebalancing look like?

U.S.-based organizations not only need to do better at looking more like their country — particularly in the corridors of power — but should also think more broadly about making sure boards, leadership, and staff reflect those they serve, and where they work.

Organizations in the sector must also move from acknowledging the need for a DEI-related policy to putting these policies in place and into action. While not an end in and of themselves, policies signal that DEI is a priority and provide the opportunity to hold leadership to account.

Where do we go from here?

Now that some baseline data exists, action is required to bridge the gap between what is and what should be. Data must lead to conversations within organizations and within the sector. And those conversations must lead to individual and collective action. Ownership at the organizational level will take commitment and resolve of leaders and boards.

To succeed, we will also require accountability and transparency at the industry level. BRIDGE survey findings make clear that a vast majority of organizations in our sector do not report diversity data publicly, and many do not share it internally. This is hiding the problem. Funders may engage in this discussion and create incentives for change, but we recognize that they are plagued by similar inequities.

We will need organizations in our sector to begin sharing their diversity data publicly and to create pressures that shift the needle in the direction of greater equity.

The survey is one small piece of a puzzle that many others are also beginning to contribute to. Through the data, our cohort of organizations aims to generate meaningful — and likely uncomfortable conversations — within organizations, with boards, and with each other in the sector.

The findings of this survey are important. If we embrace them — and most importantly use them — the survey will provide a starting place for the action that we must take and will serve as a launchpad for the difficult discussions we must have about how we can, and should, hold each other — individually and collectively — accountable for changing our organizations and our sector for the better.